'Part of Our Natural Heritage'

|

Issue:

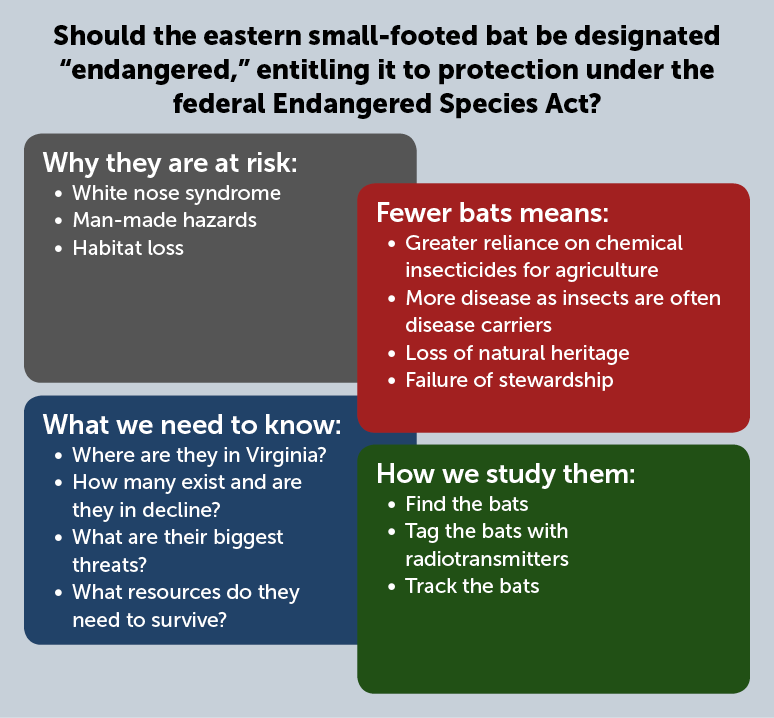

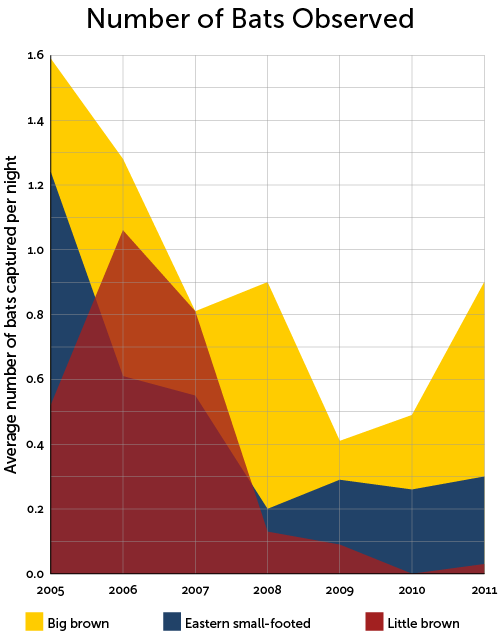

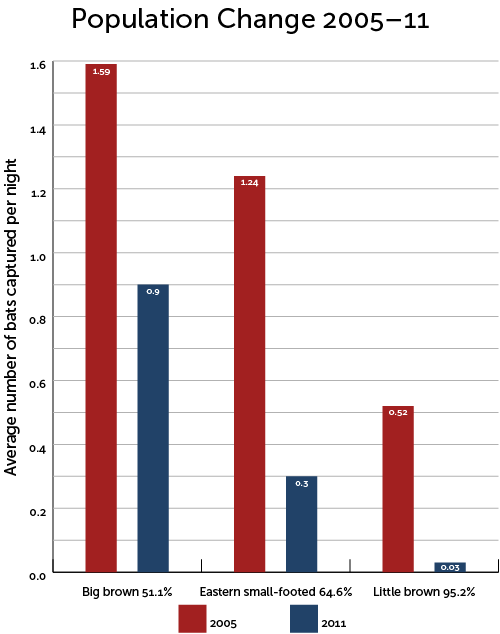

White nose syndrome, a disease that is fatal to bats, has been decimating bat populations in the eastern United States since 2006. The eastern small-footed bat is likely affected, but very little is known about the species. Lt. Col. Paul Moosman Jr. ’98, associate professor of biology, is attempting to learn more about this bat species, and especially the state of its population, in order to help agencies like the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service understand the health of the species' populations. The species is one of the rarest mammals in the world, and biologists know next-to-nothing about its ecology.

What’s been done:

Moosman and his cadet researchers are currently studying bat populations at a talus slope in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. In the past, scientists have attempted to ascertain bat populations by going into caves in the winter and counting bats there, but that method may not give an accurate population estimate for the eastern small-footed bat. Moosman is attempting to tag the animals with radio transmitters so their whereabouts can be tracked.

| Turning Students into Scientists |

| What's Cool About Bats |

Impacts:

This study stands to influence whether or not the eastern small-footed bat is designated as endangered and entitled to protection under the federal Endangered Species Act. Bats are an integral part of the ecosystem because they eat insects that are agricultural pests. Fewer bats would mean a greater reliance upon toxic chemical sprays to kill pests on crops grown for food. A sizable decline in the bat population might also have implications for human health, as insects are vectors for many human diseases. Bats only have one offspring per year, so rebuilding their population after a sharp decline will take many years.

Funding:

Grant from the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries

Contact:

Lt. Col. Paul Moosman Jr. '98, associate professor of biology, 464-7433, moosmanpr@vmi.edu

|

|

.svg)

.png)