Rat Brains and Betta Fish Support Lab Learning

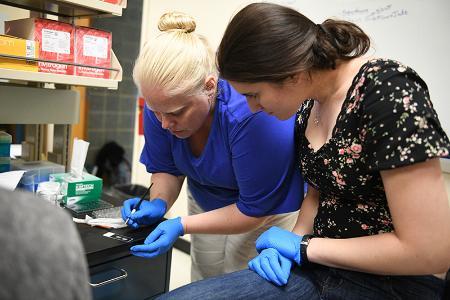

Gabby Handford '24 and Maj. Molly Kent prepare sections of a rat brain for study under a microscope.—VMI Photo by Kelly Nye.

LEXINGTON, Va., August 11, 2021—Maj. Molly Kent’s neuroscience lab is a busy place this summer, with multiple cadets working on multiple projects split over the two summer sessions. But despite their wide-ranging projects, the cadets share a common bond: a desire to learn lab skills and grow as scientists.

Kent, assistant professor of biology, came to VMI in the fall of 2020 from the University of Richmond, where she was involved in a research project in which lab rats were taught to drive tiny, rodent-sized cars. The rats, many of whom became very adept drivers, were allowed to live out their natural lifespans. Now, their preserved brains have come to Kent’s lab for study so cadets can compare the brains of rodent drivers with the brains of rats who never learned to drive.

Another project in the lab this summer includes studying differences between the brains of lead-exposed rats and rats without lead exposure. A third rodent-related initiative has to do with examining the brains of rats who’ve had plenty of bedding in their cages as youngsters versus those who’ve had little. It’s a way of mimicking high versus low socioeconomic statuses among humans, and learning how scarcity affects brain development, as well as how animals respond in terms of stress and resilience.

Unlike some labs in which specific cadets are assigned to certain projects, in Kent’s lab everyone does a little of everything and helps with all of the experiments currently underway. Kent’s goal is to allow the students to learn as many techniques as possible during their summer session, specifically during their first summer in the lab.

“I’ve really been able to learn by doing,” said Gabby Handford ’24, who began working in Kent’s lab last fall, just a few weeks into her 4th Class year. Since she’d developed an interest in neuroscience in high school, signing up for a class with Kent and working in the lab seemed a natural fit.

This summer, Handford has learned new skills as she examines the brains of the rats who’ve had abundant versus deprived environments. Using a brain scanning technique, Handford is able to analyze a hormone associated with resilience in the brains of rats.

“It’s been pretty cool,” she said. “Dr. Kent showed me how to use ImageJ, a software analysis tool, to analyze the images.”

She’s also learned a process known as isotropic fractionation, which Kent and the cadets more commonly call “making brain soup.” To make brain soup, students homogenize a brain area called the diencephalon, which includes the thalamus and hypothalamus, both needed for sensory and hormonal processing. Once the brain area is homogenized into brain soup, the total cells are counted under the microscope. The final step is to identify only neurons in the brain area by examining them under a microscope and counting cells again.

“I’m really glad I’m learning the research skills early,” said Handford, who plans to attend medical school. “I’ve got two more summer sessions and three more years of research here. I feel very lucky to end up in the lab where I want to work for the rest of my VMI career.”

Sam Wolfe ’23 is likewise happy to be learning new skills in the lab. He’s taken two classes with Kent—endocrinology and neuroscience—and now he’s applying what he’s learned. “All of the stuff we’d been talking about, we’re all of a sudden doing and seeing,” said Wolfe.

Some of the techniques Wolfe has picked up this summer have been learning to perform an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test, and doing two kinds of stains on brain cells: NeuN and Golgi. The NeuN stain is used to identify proteins found in neurons; the Golgi stain is used for analyze neurons for shape and size. The ELISAs Wolfe and the other cadets did this summer allowed them to measure hormone levels from different animal subjects. They were able to measure the stress hormone cortisol and a resiliency hormone called DHEA to see if the amount of bedding during early life can affect an animal’s resilience to stress.

“I think the research skills are important because it’s like education—knowing something and not just in a factual way,” said Wolfe, who is thinking of becoming an Army doctor. “It’s a different type of learning.”

Both Enero Ugalde ’22 and Jon Tobin ’22 have found collaborating with others to be one of the most valuable aspects of working in the neuroscience lab. “There’s a good vibe in this lab,” Ugalde commented. “Dr. Kent is awesome.”

“It’s one of the pleasant surprises being in the lab this year, knowing there’s so many different projects going on,” said Tobin. “I’m grateful to be here with my peers and with people who share the same desire for academic excellence. It’s nice to have that community in the lab.”

Both cadets are using the summer to get a head start on research that they’ll continue during their final year at VMI. For Ugalde, a double major in biology and psychology, that involves a project having to do with involving cognitive training and neuroplasticity, or the concept that the brain can change in response to experiences. During the academic year, he plans to take a group of cadets, perhaps a sports team, and measure their performance before and after completion of a series of online games designed to improve brain function in certain areas.

Ugalde has also enjoyed the chance to try new things this summer. “I’ve just today learned how to make the [brain soup],” he said. “That’s honestly one of the coolest things we’ve done.”

Tobin, meanwhile, is working with betta fish, which live in small, individual tanks in Kent’s lab. He’s planning to write his Institute Honors thesis on how acute stress can induce certain behavioral patterns and genetic expressions among betta fish.

It’s rather easy to stress a fish: all you have to do is chase them around their tanks a bit, or in the case of the aggressive betta fish, show them to each other. Currently, the fish are kept so they can’t see each other, but later on, Tobin plans to position their tanks so they can see, for the first time since they arrived at VMI, that they aren’t the only fish in the room.

Once the fish have seen each other, Tobin plans to measure their levels of a protein called c-Fos, which is an immediate early gene. c-Fos will allow Tobin to identify which areas of the fish brain are activated after they see another male betta. Along with brain activation, Tobin has also collected hormones to see how the brain, hormones, and behavior corollate with each other. The data will provide the team with a better understanding of how acute stress can affect an aggressive fish.

“This lab has given me the opportunity to work with live animals and study their behavior,” said Tobin, whose previous experience with fish was limited to catch-and-release fishing. “It’s kind of cool being in here and working with them for a scientific purpose.”

In the second summer session, Wolfe, along with Alex Feher ’23 and Samantha Fee ‘23 will be studying sex-linked differences in the brains of stickleback fish—an initiative that could show intriguing results, since the male stickleback takes all of the responsibility for raising the young of the species. Kyle Tidwell ’22 will also begin work on his senior thesis project, which will focus on the effect of chronic stress on betta fish.

“I want the students to learn as much as they can in a summer session, so I try to have as many different projects as I can to facilitate that,” said Kent. “Many of my students plan to continue their education after VMI, be that in medical school or graduate school, and I want to help prepare them for those future endeavors by teaching them hands-on techniques that they might not see in class. They also participate in designing experiments, so that they know to always ask questions and strive to understand science.”

Mary Price

Communications & Marketing

VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE

.svg)

.png)